The Diagnosis Trap: Why More Americans Are Mentally Ill on Paper Than in Reality

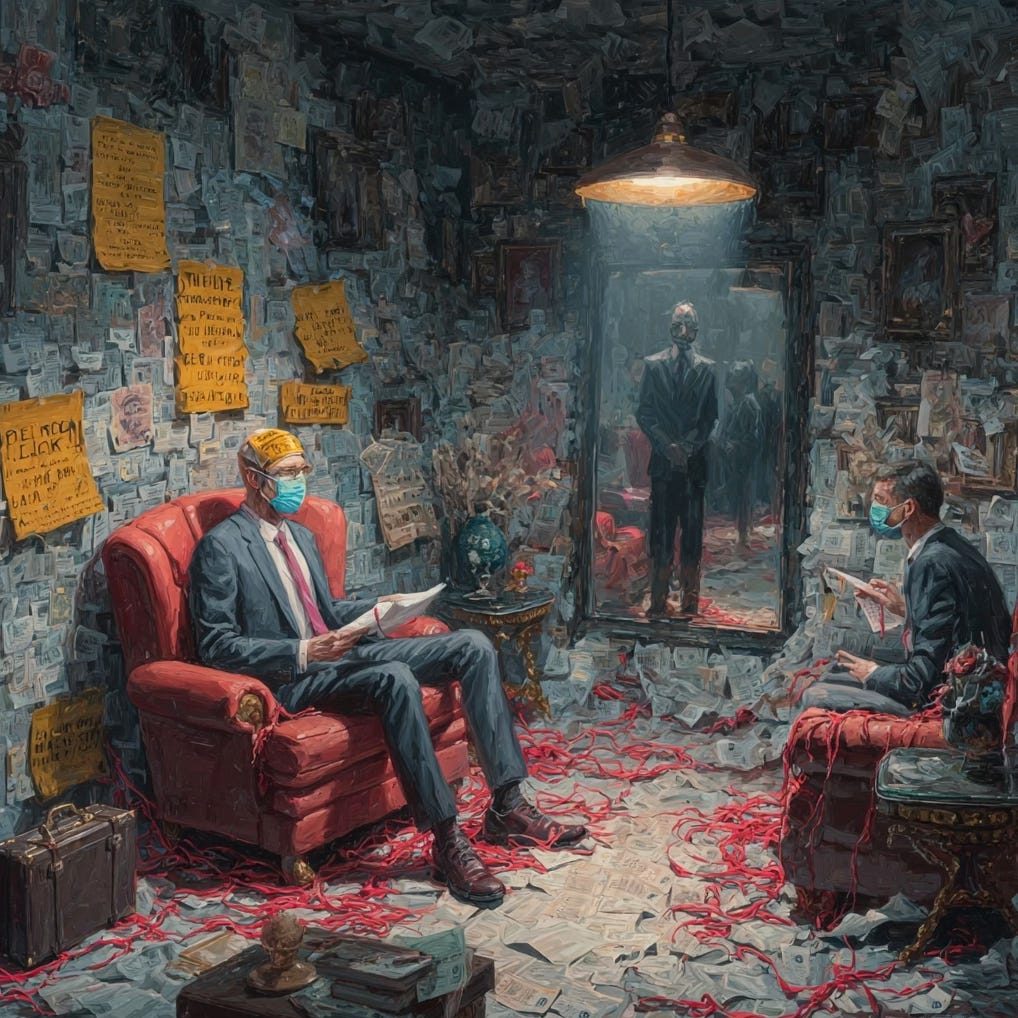

We’re not in a mental health crisis. We’re in a meaning crisis—coded, billed, and reimbursed one disorder at a time.

Diogenes In Exile is reader-supported. Keep the lamp of truth burning by becoming a paying subscriber—or toss a few drachmas in the jar with a one-time or recurring donation. Cynics may live in barrels, but websites aren’t free!

Overdiagnosed by Design

For years, headlines have warned of a growing mental health crisis. Some reports claim that as many as 1 in 5 U.S. adults have received treatment in the past year. But what if that figure says less about the mental health of Americans and more about how we define, incentivize, and diagnose disorder?

In March 2025, UK Health Secretary Wes Streeting warned that too many people were being "written off" by mental health diagnoses that may not reflect genuine clinical conditions. That wasn’t new. Concerns about overdiagnosis in the U.S. stretch back at least to 2013, with studies showing a steady uptick in diagnoses from 2007 to 2022.

So what exactly is overdiagnosis?

According to BetterHelp:

“Overdiagnosis can occur when a mental healthcare provider tells someone they have a mental health condition that they do not have… often resulting from broad diagnostic criteria or increased medical scrutiny.”

In practice, this affects diagnoses like:

Major depressive disorder

Bipolar disorder

ADHD

Anxiety

Autism spectrum disorders

Personality disorders

Conduct disorders

These conditions are typically diagnosed based on subjective symptoms, feelings, thoughts, and behaviors, which creates enormous variability in interpretation. Unlike a broken leg, which is objectively the same in Tasmania as it is in Salzburg, what qualifies as “disordered” thinking or feeling is deeply shaped by culture, ideology, and even trends.

Once, hearing voices might have made you a prophet. Today, it might get you institutionalized. Diagnostic standards are not stable truths, they’re shifting social judgments codified by consensus.

Misdiagnosis is a risk. But overdiagnosis is systemic.

If you think it’s just a few undertrained therapists making bad calls, you’re missing the bigger picture. When an entire ecosystem, from reimbursement to regulation, is aligned to reward diagnosis, diagnosis becomes inevitable.

Show Me the Money

Therapy has always had a legitimacy problem: How do you charge money for something you can’t measure? Before the Affordable Care Act, access was limited and more often out-of-pocket. But with expanded coverage came a new economy—one that included formal diagnosis for reimbursement.

Here’s the catch: insurance doesn’t pay for “talking through a rough patch.” It pays for treatable conditions. That means if your dog died, your partner is cheating, or your life just feels off, none of that justifies a claim. But if those experiences are reframed as clinical depression, adjustment disorder, or anxiety? Now we’re talking.

To get paid, therapists must diagnose. No code, no check. The DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) isn’t just a tool; it’s a tollbooth where therapists code symptoms, submit claims, and repeat. The more ongoing the problem, the more justifiable the treatment. For clients, that process is mostly invisible. They show up. They talk. They leave. But in the background, a billing trail begins, one that may permanently label them with a disorder they were never told was optional, and crucially, the DSM has no codes for “cured.”

Once diagnosed, always diagnosed.

Defensive Diagnosis

If billing incentives push therapists to find a diagnosis, legal threats practically shove them off the cliff.

Therapists today must not only treat, they must protect themselves from liability. If a client deteriorates after clients leave the office, failing to have “appropriately diagnosed” them can be grounds for a lawsuit or licensure challenge. Defensive diagnosis becomes a smart move.

In some jurisdictions, it’s gone further. Laws banning so-called “conversion therapy” now include gender identity, criminalizing any effort to explore alternative origins of dysphoria, like trauma, internalized homophobia, or identity disorders. Even asking certain questions is off-limits. The result? Therapists affirm without pushback, putting clients through the gates on the short path toward surgery.

The law has done what ideology alone could not: it has hard-coded one worldview into clinical protocol, even when that worldview contradicts the patient’s long-term best interest and the bulk of scientific investigation.

It’s legal compliance masquerading as care.

Obey the Ideology

Clinical training itself has not escaped this trend. Today’s graduate programs often center DEI frameworks and Critical Social Justice dogma, not just as lenses, but as foundations, with patients increasingly assessed not by what’s wrong with them, but by who they are. Race, gender, sexuality, and perceived oppression are treated as clinical facts.

In this worldview, a cis Black gay man could be diagnosed with PTSD due to internalized oppression and colonial trauma in addition to or in place of the obsessive habits that brought him into the office.

Thousands of therapists trained this way are entering the workforce each year. Many are joining licensure boards, professional associations, honor societies, and advising on legal policy at the highest level of government. Therapists who dissent risk being reported, ostracized, or investigated, not for malpractice, but for ideological noncompliance.

The incentive is clear: conform, affirm, and label. And never ever suggest that the problem might be deeper than identity.

Clients as Consumers—and Products

Of course, therapists aren’t acting alone. Many clients today come into therapy already self-diagnosed, with a diagnosis in hand, courtesy of TikTok, Reddit, or Instagram. They’re not looking for insight. They want validation—and a clinical stamp of approval.

For them, a diagnosis isn’t a disorder. It’s a brand.

The affirming model of therapy, quickly coming to dominate training programs, ignores the value of painful introspection and rewards identification with pathology. The more attached a person becomes to their diagnosis, the less likely they are to part with it. It becomes part of their self-concept. And that makes them a perfect consumer: compliant, dependent, and renewable.

In this model, healing becomes a liability. A truly effective therapist might face accusations of invalidation or “harm.” Meanwhile, institutions that profit from ongoing treatment would lose money, prestige, and relevance every time a client recovers.

The Upshot

This isn’t just a mental health crisis. It’s a misaligned system functioning exactly as designed.

It rewards overdiagnosis. It rewards chronic treatment. It rewards ideological conformity and punishes clinical dissent.

Practitioners who want to help people heal are working against the tide. Clients who want truth may have to fight through a system that’s incentivized to sell them identity, not agency.

Overdiagnosis is just the symptom.

Further Reading

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision Dsm-5-tr by the American Psychiatric Association

Help Keep This Conversation Going!

Share this post on social media–it costs nothing but helps a lot.

Want more perks? Subscribe to get full access to the article archive.

Become a Paid Subscriber to get video and chatroom access.

Support from readers like you keeps this project alive!

Diogenes in Exile is reader-supported. If you find value in this work, please consider becoming a pledging/paid subscriber, donating to my GiveSendgo, or buying Thought Criminal merch. I’m putting everything on the line to bring this to you because I think it is just that important, but if you can, I need your help to keep this mission alive.

Already a Premium subscriber? Share your thoughts in the chat room.

About

Diogenes in Exile began after I returned to grad school to pursue a master’s degree in Clinical Mental Health Counseling at the University of Tennessee. What I found instead was a program saturated in Critical Theories ideology—where my Buddhist practice was treated as invalidating and where dissent from the prevailing orthodoxy was met with hostility. After witnessing how this ideology undermined both ethics and the foundations of good clinical practice, I made the difficult decision to walk away.

Since then, I’ve dedicated myself to exposing the ideological capture of psychology, higher education, and related institutions. My investigative writing has appeared in Real Clear Education, Minding the Campus, and has been republished by the American Council of Trustees and Alumni. I also speak and consult on policy reform to help rebuild public trust in once-respected professions.

Occasionally, I’m accused of being funny.

When I’m not writing or digging into documents, you’ll find me in the garden, making art, walking my dog, or guiding my kids toward adulthood.

So many mental "disorders" would be cured by regular exercise, making friends, and finding a sense of purpose. All 3 of these have each been shown to be equal to antidepressants in terms of their impact on mental well-being. Since scientists realized the link between neurochemicals and thoughts, they seem to be obsessed about using chemicals to influence thoughts, when really they should be finding ways to think and act that restore the underlying chemical balance. Of course, so much of this has to do with the way mental health is funded, as you point out.

Please check out *Anatomy of an Epidemic* by Robert Whitaker.

It's so bad; people have no idea.