Social Work's "Compassionate" Bait-and-Switch

How New Professionals are Roped into Ideology, Not Honest Preparation

Diogenes In Exile is reader-supported. Keep the lamp of truth burning by becoming a paying subscriber—or toss a few drachmas in the jar with a one-time or recurring donation. Cynics may live in barrels, but websites aren’t free!

Editorial Note: This essay is the second of three in which I uncover the failings of contemporary social work education. All three are dedicated to my brother–and to all who refuse to let their group identity speak for them. Part 1, Part 3.

Social work education has been featured in the news this Winter, and not in a positive light. First, an exposé came out about sex- and race-based discrimination under the banner of “anti-racism”. Then came a specious defense of a suspended social work professor that lectured on the “pyramid of White supremacy,” ignoring the hyper-politicized “progressive” origin of the pyramid itself. Finally, a damning report was released in December about social work’s compelled use of “anti-racism, diversity, equity, and inclusion” in the classroom.

All of these are part and parcel of social work education’s national pivot towards an intolerant, socially regressive ideology operating in the name of faculty-backed “progressivism.” Last week, I published two students’ experiences in their Masters of Social Work (MSW) programs paying to “learn” about this progressive ideology, all at the cost of adequate professional preparation.

This week, I draw on my own MSW experience at Colorado State University (CSU) to show how students of any political persuasion can get hooked by social work’s seemingly innocuous language of “compassion,” only to find themselves thrown into an ideologically sealed world with little ability to push back or fruitfully disagree.

Normally, an essay like this would include student perspectives from other universities, but public criticism of social work programs by students is virtually non-existent. What’s more, after the “Whitelash” story broke in October in Minding the Campus, the overwhelming majority of my 30-person program cohort at CSU distanced themselves from me in the weeks following. Those that stay in touch do so under the desire for anonymity, which I wholeheartedly respect.

In my case, social work was my first and only choice in Fall 2022 for going back to get a Master’s degree. I had heard positive things about the profession’s versatility from friends and co-workers, anchored in identifying ways that a person’s environment could contribute to their life difficulties. My choice had been solidified after learning about the beauty of hospice social work as I cared for those with dementia. I was there to learn and to help.

“From the very start, I was hooked on the field’s person-in-environment (PIE) framework,” I wrote about my experience. “And I was ready to set aside the tainted impressions of social work from the media and from grandiose BSW students I met from undergrad.”

On the first day of class, after going over the syllabi, we talked about social work’s checkered history of splitting people into “deserving” and “undeserving”. (Links to syllabi for two required classes can be found here and here. The ideological slant was glaringly obvious from the beginning, mirroring a recent study on slanted syllabi and “closed classrooms”). Having learned about historical social divisions within American society, this made sense. Professors implied that social workers were compassionate, accepting, and advocate for all people—no matter what. Most of the students in my cohort—myself included—seemed to hold a moral intuition that something ought to be done to reduce the sum total of suffering in American society.

Educators’ Hidden Agenda

It turned out that this was the first of three “bait-and-switch” strategies that social work professors undertook during the first semester—completely kosher by the program’s national accrediting body, as my colleague Arnoldo Cantú and I found out, after the release of the discipline’s 2022 Education Policy and Practice Standards (EPAS):

Bait #1: Draw students and the public in with the language of compassion and understanding on behalf of all people.

Switch #1: Dictate to both groups that the primary role of the social worker is group-obsessed activism, liberation, and anti-oppressive practice (the latter being a code word for the openly post-Marxist and socialist concept, ‘radical democracy’.)

Bait #2: Appeal to students and the public by speaking to universal experiences of pain and suffering.

Switch #2: Dictate to both groups that individualism, racism, heterosexism, colonialism, capitalism, White people (etc.) are the only credible causes of human suffering.

Bait #3: Draw students and the public in with language of fairness, equality, and social justice.

Switch #3: Delegitimize the possibility of realistic fairness and individual equality. Dictate to both groups that critical social justice—with embedded critical race theory—is the only correct form of thinking. Ignore or directly undermine liberal, conservative, capability, or religious forms of social justice.

To be sure, if one zooms out with a Big history and world history lens, any society and country on Earth—including the United States—can be cruel, filled with historical slavery, violence, and war. Contemporary conflicts abound. Individual pain, no matter who one is, can be overwhelming, hence ongoing ethical debates about the reasonability of suicide. Suffering can seem universally never-ending.

Yet, likely because of social work’s strong psychological focus, none of this historical nuance and realism about the human condition was discussed, much less an honest take about the sociopolitical complexity of American ideas around suffering, compassion, fairness, equality, and competing forms of justice.

The bait appeared to hook most students in. Problems in American society had “progressive” causes that led to “progressive” solutions. Moderate, conservative, or libertarian views were written off, vilified, or silenced through subtly enforced classroom norms that insisted, “This is not what real social workers believe.” According to the class syllabus mentioned above on “Anti-Oppressive Social Work Practice,” it was up to social workers to “combat stereotypes, myths and discriminatory attitude[s], and injustice.” Political diversity—outside of the accepted intolerant and illiberal far-left “progressive” viewpoints—became one of the primary targets that, in professors’ eyes, we as new social workers should work to combat. Anything remotely related to the “status quo” was intolerable. (This, despite the fact that progressive activism constitutes a minority viewpoint across the United States compared to the “exhausted majority.”)

The Road to Graduation

I split the difference, justifying the enormous cost of classes by searching for measly morsels of truth and wisdom that could be carried forward into practice (this was supposed to be preparation to be a professional, after all). Questions about the holes in our education constantly tugged at my conscience. What happens when social work’s governmental money tree withers? What about people who have been viewed as taking advantage of the system, without bearing any of the costs? Where was the realistic conversation about ethics and decision-making? About scene safety, especially when we have no choice but to work with people who are uncontrollably violent? About the economic growth and innovation that water the profession’s money tree? What about “minorities” that reject social work’s accusatory, group-identity narrative? Does social work have any meaningful response to the exclusionary hierarchies of global order, ones that have been there cyclically for centuries?

(Crickets. The typical answer we heard was that we “don’t have time” or that these questions would be “discussed in field,” i.e. our internship).

Barry Latzer, I later learned, raised the same points back in 2007:

A social worker who is largely ignorant of American history faces an intellectually blinkered professional life in which there will be strong temptation to respond to problems according to the stereotypes and shibboleths of the moment. A social worker who is largely ignorant of political theory is unarmed against the appeals of demagogues who offer simplistic and sometimes unconstitutional remedies to complex problems. A social worker with no grounding in philosophy likewise is ill equipped to tell the difference between cogent reasoning and ideology, which superficially can look alike. A social worker not conversant with economics will be in a poor position to evaluate different approaches to the alleviation of poverty.

I had also split the difference before I even started school, experimenting with social work’s compassion- and group-centered language (italicized below) in an end-of-life research lab biography. After realizing the degree to which this signaled group-based identity politics and progressive “luxury beliefs,” I now consider this way of thinking to be a big mistake:

Nathan’s interest in the end-of-life journey comes from his previous work as a caregiver for people with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. In particular, he is focused on issues surrounding financial access, choice, and agency during the end-of-life process. He is also passionate about holding space for stories across the LGBTQ+, Latinx, and mental health communities. In addition to his role as a Graduate Research Assistant, Nathan is a Certified Nurse’s Aide (CNA) – Behavioral Health Technician (BHT) for UCHealth in Northern Colorado.

Fast forward three years later.

The summer after graduation and revealing myself as the pseudonymous author of “Out of Balance,” a School of Social Work employee directly questioned my values as a new social worker and whether, in their words, “I cared about meeting the individual where they are at.” (This, despite the person knowing I worked through school as a hospital nursing assistant and interned as a hospice social worker. Both are jobs that explicitly demand meeting individuals physically, emotionally and spiritually “where they are at.”)

Speaking Out

It turns out this was a fourth bait-and-switch, the same thing befalling a PhD student in the same program.

Bait #4: Appeal to the discipline’s care-oriented “values” to justify the credibility of the profession.

Switch #4: Dictate to new and seasoned professionals that values steeped in critical social justice take priority over the other five values in our profession’s Code of Ethics. Demand that “dismantling White supremacy” and “decolonizing social work” constitute the only way forward.

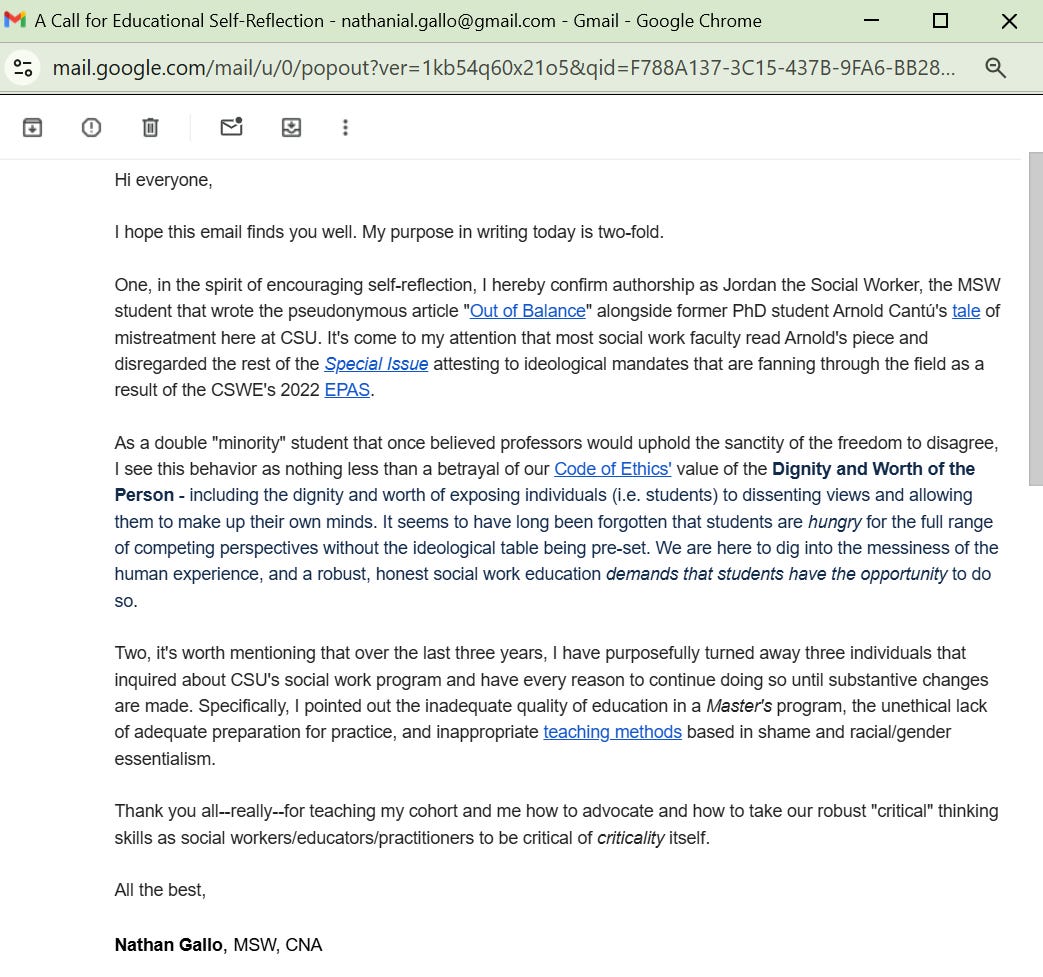

This incident led me to reveal my identity publicly and send the following email in October 2025 to the School of Social Work’s faculty and staff (email addresses are removed to preserve confidentiality). I wrote with impassioned enthusiasm after realizing the extent to which our cohort had fallen for the stack of bait-and-switches, missing out on a quality professional education that took an honest account of the full range of sociopolitical ideas. The email was titled A Call for Educational Self-Reflection and remains unanswered to this day:

Social work can hardly be the only educational discipline that is overdue for correction. Higher education itself is in desperate need of heterodox students to write about their experiences, creating a record trail that can help spur reform—especially in disciplines tied to formal professions. As the work that Suzannah has done on this Substack illustrates, it will take students from all of the helping professions—counseling, psychology, psychiatry, marriage and family therapy, psychiatric nursing—to expose and dress down this ideologically rigid set of bait-and-switches. After all–teaching by professionalism, not ideological conformity, is the most humane way forward.

Nathan Gallo, MSW, CNA is a recent Master of Social Work graduate and hospital nursing assistant based in Northern Colorado. He has written about the importance of cognitive liberty, tolerance and value pluralism in social work education. Gallo also led a case study article on medical aid in dying (MAID) and motor neuron disease, published in the flagship journal for this practice, The Journal of Aid-in-Dying Medicine.

Help Keep This Conversation Going!

Share this post on social media. It costs nothing but helps a lot.

Become a subscriber. Higher subscriber numbers would draw in guest writers and interesting folks for interviews.

Want more perks? Become a Paid Subscriber to get chatroom access and let’s talk about what else Diogenes In Exile can do.

Support from readers like you keeps this project alive!

Diogenes in Exile is reader-supported. If you find value in this work, please consider becoming a pledging/paid subscriber, donating to my GiveSendgo, or buying Thought Criminal merch. I’m putting everything on the line to bring this to you because I think it is just that important, but if you can, I need your help to keep this mission alive.

Already a Premium subscriber? Share your thoughts in the chat room.

About

Diogenes in Exile began after I (Suzannah Alexander) returned to grad school to pursue a master’s degree in Clinical Mental Health Counseling at the University of Tennessee. What I found instead was a program saturated in Critical Theories ideology—where my Buddhist practice was treated as invalidating and where dissent from the prevailing orthodoxy was met with hostility. After witnessing how this ideology undermined both ethics and the foundations of good clinical practice, I made the difficult decision to walk away.

Since then, I’ve dedicated myself to exposing the ideological capture of psychology, higher education, and related institutions. My investigative writing has appeared in Real Clear Education, Minding the Campus, The College Fix, and has been republished by the American Council of Trustees and Alumni. I also speak and consult on policy reform to help rebuild public trust in once-respected professions.

Occasionally, I’m accused of being funny.

When I’m not writing or digging into documents, you’ll find me in the garden, making art, walking my dog,

Nathan, I would love to have a chat with you sometime about all this. Ex-counseling student here, friend of Suzannah's.

Brillant essay. Kindly, Aaron Kindsvatter